And here is Ekaterina Krokhina’s second blogpost, nicely continuing her findings after the first. A good example of work in progress.

I am really very much indebted to you for your well-filled and very interesting letter (1832; Charlotte Brontё to Ellen Nussey)

I would like to start my blog post from this opening of Charlotte Brontё’s (1816–1855) letter to her best friend Ellen Nussey (1817–1897) in order to remind you, readers, how precious letters used to be for people. If we want to send a letter now, we can do it easily, as a piece of cake, although nowadays it will be most likely not a real letter but an electronic one. The attitude towards letters was completely different in the past. Have a look at the phrase above one more time and pay attention to this part “I am really very much indebted”. Don’t you think this part is a little bit overcrowded with intensifiers? Still the intensification is not finished yet, we can see that “well-filled and very interesting” are coming next. After coming across this “over- intensified” sentence and a few similar ones, I decided to check the whole first volume of Charlotte Brontё’s correspondence. I was particularly interested in her use of intensifiers. To my surprise it turned out that very was the most frequent intensifier in her letters. Charlotte Brontё also used most but not as often as very. In the first volume of her correspondence she used very 415 times and most only 127 times.

I would like to start my blog post from this opening of Charlotte Brontё’s (1816–1855) letter to her best friend Ellen Nussey (1817–1897) in order to remind you, readers, how precious letters used to be for people. If we want to send a letter now, we can do it easily, as a piece of cake, although nowadays it will be most likely not a real letter but an electronic one. The attitude towards letters was completely different in the past. Have a look at the phrase above one more time and pay attention to this part “I am really very much indebted”. Don’t you think this part is a little bit overcrowded with intensifiers? Still the intensification is not finished yet, we can see that “well-filled and very interesting” are coming next. After coming across this “over- intensified” sentence and a few similar ones, I decided to check the whole first volume of Charlotte Brontё’s correspondence. I was particularly interested in her use of intensifiers. To my surprise it turned out that very was the most frequent intensifier in her letters. Charlotte Brontё also used most but not as often as very. In the first volume of her correspondence she used very 415 times and most only 127 times.

Mustanoja reports that ongoing renewal of popular intensifiers happens all the time. The first shifts can be traced back to the twelfth century (1960, p. 319), as illustrated in this overview:

As the table shows, there were two main intensifiers really and very, which were the most common in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Charlotte Brontё was obviously in favour of very, using really only 55 times in the first volume of her letters. Her usage of really is 7.5 times lower than that of very, interesting, isn’t it?

My first blog post, was devoted to Charlotte Brontё’s usage of most. At that time I couldn’t answer the following question: Why did she use most as an intensifier? Now, I would like to suggest that she used most as a semantic synonym of very. These two intensifiers (with the exception of cases where most served as a superlative) were sort of interchangeable in her letters.

Here are some examples:

- I feel most anxious to learn how matters progress (Charlotte Brontё to Ellen Nussey, 1845)

We feel very dull without you (Charlotte Brontё to Ellen Nussey, 1840)

- On that day we shall all be most happy to see you, and till then believe me to be (Charlotte Brontё to Ellen Nussey, 1833)

We shall be very happy to wait upon yourself and Sister… (Charlotte Brontё to Miss Ann Greenwood, 1836)

- ….and very welcome messengers they are (Charlotte Brontё to Ellen Nussey, 1845)

Your letter and its contents were most welcome (Charlotte Brontё to Ellen Nussey, 1847)

You must excuse a very short answer to your last most welcome letter (Charlotte Brontё to Ellen Nussey, 1841)

These examples show that Charlotte Brontё indeed used very and most quite interchangeably.

According to Quirk et al. (1985), the most rapid and the most interesting semantic developments in linguistic change are said to occur with intensifiers (1985, p. 590), and Peters (1994) claims that “[t]his area of grammar is always undergoing meaning shifts partly because of speaker’s desire to be original” (1994, p. 271). I assume that Charlotte Brontё was also quite “original” in her use of intensifiers. In any case, she was clearly in favour of them.

References:

Brontë, C. The letters of Charlotte Brontë: with a selection of letters by family and friends (1829-1847). M. Smith (ed.). Vol. 1. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Mustanoja, T.F. (1960). A Middle English syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique.

Peters, H. (1994). Degree adverbs in early modern English. In Dieter Kastovsky (ed.), Studies in Early Modern English, 269–88. Berlin & New York: Walter de Gruyter.

Quirk, R., Greenbaum, S., Leech, G. & Svartvik, J. (1985). A comprehensive grammar of the English language. New York: Longman.

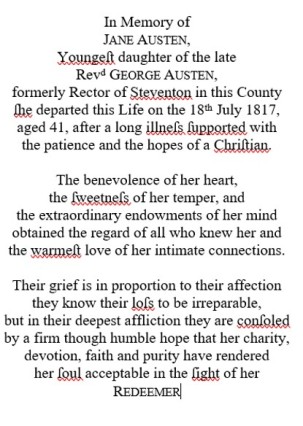

Jane Austen is op 18 juli 1817 overleden, waarschijnlijk aan de gevolgen van de ziekte van Hodgkin. Dat gebeurde in Winchester, waar ze voor medisch advies naartoe was gebracht. Ze is ook in Winchester begraven, zonder dat haar moeder en haar zus Cassandra daarbij aanwezig mochten zijn: begrafenissen waren een mannen-aangelegenheid. Haar grafsteen ligt daar in de kathedraal, met een tekst die waarschijnlijk door haar broer Henry is opgesteld, maar die geen recht doet aan haar schrijverschap.

Jane Austen is op 18 juli 1817 overleden, waarschijnlijk aan de gevolgen van de ziekte van Hodgkin. Dat gebeurde in Winchester, waar ze voor medisch advies naartoe was gebracht. Ze is ook in Winchester begraven, zonder dat haar moeder en haar zus Cassandra daarbij aanwezig mochten zijn: begrafenissen waren een mannen-aangelegenheid. Haar grafsteen ligt daar in de kathedraal, met een tekst die waarschijnlijk door haar broer Henry is opgesteld, maar die geen recht doet aan haar schrijverschap.

Het is echt prachtig, maar er is van alles mee mis: Jane Austen heeft er bijvoorbeeld nooit zo uitgezien. We hebben maar één echt portret van haar, geschilderd door haar zus Cassandra, en daarop ziet ze er tenminste niet uit als een tienjarig meisje:

Het is echt prachtig, maar er is van alles mee mis: Jane Austen heeft er bijvoorbeeld nooit zo uitgezien. We hebben maar één echt portret van haar, geschilderd door haar zus Cassandra, en daarop ziet ze er tenminste niet uit als een tienjarig meisje:

I would like to start my blog post from this opening of Charlotte Brontё’s (1816–1855) letter to her best friend Ellen Nussey (1817–1897) in order to remind you, readers, how precious letters used to be for people. If we want to send a letter now, we can do it easily, as a piece of cake, although nowadays it will be most likely not a real letter but an electronic one. The attitude towards letters was completely different in the past. Have a look at the phrase above one more time and pay attention to this part “I am really very much indebted”. Don’t you think this part is a little bit overcrowded with intensifiers? Still the intensification is not finished yet, we can see that “well-filled and very interesting” are coming next. After coming across this “over- intensified” sentence and a few similar ones, I decided to check the whole first volume of Charlotte Brontё’s correspondence. I was particularly interested in her use of intensifiers. To my surprise it turned out that very was the most frequent intensifier in her letters. Charlotte Brontё also used most but not as often as very. In the first volume of her correspondence she used very 415 times and most only 127 times.

I would like to start my blog post from this opening of Charlotte Brontё’s (1816–1855) letter to her best friend Ellen Nussey (1817–1897) in order to remind you, readers, how precious letters used to be for people. If we want to send a letter now, we can do it easily, as a piece of cake, although nowadays it will be most likely not a real letter but an electronic one. The attitude towards letters was completely different in the past. Have a look at the phrase above one more time and pay attention to this part “I am really very much indebted”. Don’t you think this part is a little bit overcrowded with intensifiers? Still the intensification is not finished yet, we can see that “well-filled and very interesting” are coming next. After coming across this “over- intensified” sentence and a few similar ones, I decided to check the whole first volume of Charlotte Brontё’s correspondence. I was particularly interested in her use of intensifiers. To my surprise it turned out that very was the most frequent intensifier in her letters. Charlotte Brontё also used most but not as often as very. In the first volume of her correspondence she used very 415 times and most only 127 times.