Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Leiden University Centre for Linguistics

“No new letters by Jane Austen have been found since the publication of the third edition in 1995,” Deirdre LeFaye concludes in her introduction to the fourth edition of Jane Austen’s correspondence (2011, p. xvi). Unfortunately not, but sometimes parts of letters come to light that were previously known to have existed but that have since disappeared, or her letters change hands, and when they do, they invariably hit the news. The first thing happened with a scrap of a letter that had found its way into a scrapbook. The scrapbook had turned up at an auction, was acquired by an unknown buyer, but was temporarily on display at Jane Austen’s House Museum in Chawton, England, when I happened to visit in the summer of 2019.

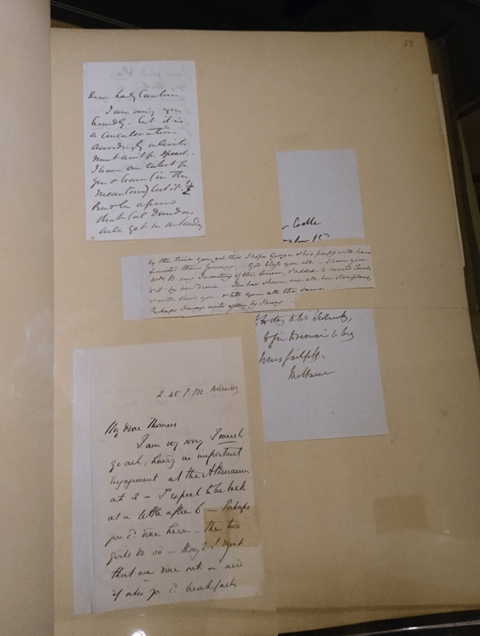

Scrapbook with part of a letter by Jane Austen (middle), Jane Austen’s House Museum, summer 2019 (© Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade)

Part of another letter had recently surfaced as well, and while I was in Chawton, there was a crowdfunding appeal the museum had launched in order to be able to acquire it. The letter had been cut up at some point in its history, and the section in question had been temporarily misplaced, we read in the notes to Le Faye’s edition of the letter. Cutting up her letters was done quite often after Jane Austen had become a famous writer in response to requests from autograph hunters for mementoes of her as an author. If you look carefully at the scrap above, the signature is still missing, and who knows, it may surface at some point as well. The museum’s appeal proved successful, as the BBC reported on 20 August that year – not unexpectedly, because Jane Austen as a literary icon is today still one of the best-known novelists in the UK.

More recently, Jane Austen’s House Museum acquired a complete Jane Austen letter, Letter 10 as numbered in Le Faye’s authoritative letter collection. This time, it was not a missing letter that had come to light, but one that had been in someone’s private possession. This (further unidentified) person had run up a large tax debt – as much as £140,000, The Guardian online reported in March 2023 – and in exchange for dontating a major cultural artifact was able to settle the debt. The transaction was part of a so-called Acceptance in Lieu scheme, thanks to which the letter is now available to the general public.

Accessing the Guardian article will give an opportunity to view an image of the letter, and looking at the letter carefully will provide a good idea of Jane Austen’s lettter-writing habits, a topic I have regularly lectured about since the publication of my book In Search of Jane Austen (Oxford University Press, 2014). On the one hand, the physical image of the letter as shown by The Guardian is important because it shows how letters were folded and put into the post at a time when envelopes were not yet available. But having the letter available like this will at the same time allow us to engage in a close-reading analysis of it, not only of its contents (there is something on that in the Guardian article already) but also of letter writing practice at the time, with Jane Austen as an example, and of its language. In various interactive recent talks I made students identify the outward characteristics of the letter as shown, and on the basis of a transcription of the letter which I provided for them I made them study its language as part of a set assignment. An important tool for this analysis was the Oxford English Dictionary (OED), as in all my work on the history of the English language, which may best be illustrated from my earlier textbook Introduction to Late Modern English (2009, Edinburgh University Press).

In this introduction, I discussed first usages in the OED by individual authors from the period, men and women, to see to what extent their vocabulary had enriched the English language. This also proved informative about the authors’ private lives, so it worked both ways. The finding that the writer Samuel Richardson (c.1689–1761), for instance, wasn’t the source of any loanwords as first occurrences in the dictionary confirmed that he never travelled abroad: as the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography writes, he “seldom ventured very far from London”. My list included Jane Austen, too, who was shown to have 51 first usages of words in the OED. At the time, that is, for the dictionary is constantly being revised, and the usage history of words is adapted whenever new “firsts” are found. Newly discovered earlier usages by other writers have caused some of her firsts to disappear, though we will see that there are new ones to be found that should be added to the dictionary. It is thrilling for students to discover that through their research they can contribute to the OED, even if in a minor way.

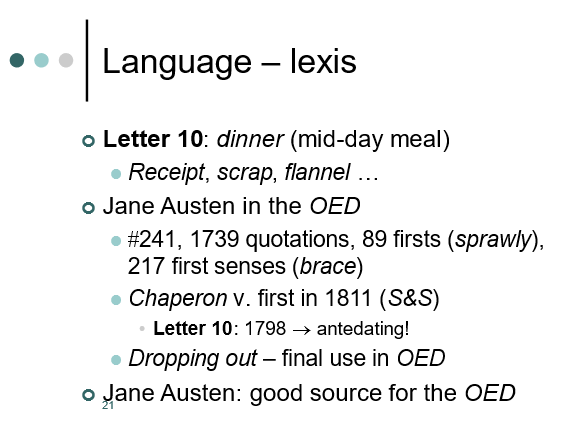

One of the results of the constant revision of the OED, however, is that a very useful tool has disappeared. This is due to the fact, as I was told recently when inquiring about this, that figures about individual authors’ usage are forever changing, so that it would be impossible to keep figures up to date. The usefulness of the tool may be illustrated as follows. In lectures on the language of Jane Austen’s letters, I used to illustrate her presence in the dictionary by providing figures like the as in this powerpoint slide (based on Letter 10).

Powerpoint slide from recent lectures on Jane Austen’s language (© Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade)

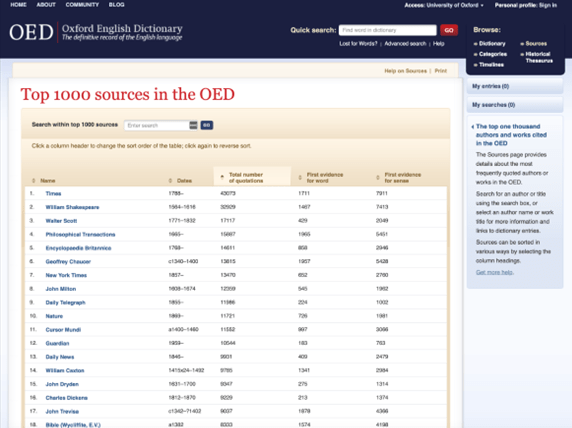

Important among the figures in this slide was the figure 241, which showed her presence among the 1000 most frequently cited authors and other sources (like The Times) for the dictionary. A screen shot of this league list, as I refer to it, may still be found on Charlotte Brewer’s highly informative website called “Examining the OED”.

Screenshot from 2019, taken from “Examining the OED”

(Jane Austen isn’t on the list here since the image only shows the eighteen most frequent sources.) Because the option is no longer available, I don’t know where Jane Austen stands in the list at the moment – there are other, more complicated which of finding out, which I won’t go into here because the point I just want to make here is how unfortunate it is that this tool is no longer there. The other figures – and findings – in my powerpoint slide are still relevant though, and I will proceed to discuss them on the basis of a linguistic close reading of Letter 10. But first I will discuss some external aspects of this fascinating letter.

The letter is one of the longest of Jane Austen’s letters. It was addressed to her sister Cassandra, and was written in the course of two days, 27 and 28 October 1798, on a single sheet. At the time, there were no postage stamps, and the recipient paid by the sheet. Nor were there any envelopes yet: letters were folded in such a way that all text was inside and only an empty panel remained for the name and address of the recipient. So Jane Austen crammed as much text as possible on a single sheet of paper, as is indeed evident from the smaller handwriting on the left of the unfolded letter in the image provided by The Guardian when she realised she was running out of space with everything she had to tell her sister. She referred to her writing being “so much more sprawly” than her sister’s (this quotation is cited as a “first” in the OED for sprawly). Folding up the letter, there was the choice of closing it with sealing wax or a wafer, but the red circle below the address panel suggests that she used the much cheaper option of the wafer: a bit of edible paper, ready-bought, that, when licked with spittle, would serve as well as sealing wax.

The style of the letter is informal, like all her letters to her sister. Letter 10 relates details about the journey home from Kent, where Jane and her mother had been staying with Jane’s brother Edward in Godmersham Park. Not an easy journey, it appeared, because her mother had become unwell halfway through and they had to call in the advice of a doctor at Basingstoke, who prescribed “12 drops of Laudanum”, a “preparation in which opium was the main ingredient”, as the OED defines the word. Being held up for a while in this market town, Jane took the opportunity of doing some shopping, but was disappointed at being unable to find “narrow Braces for Children, & scarcely any netting silk”. As with sprawly, the quotation is in the OED, this time as a so-called “first sense” for the word brace, defined as “a pair of straps of elastic, leather, etc., which pass over the shoulders and are fastened to the front and back of the waistband of a pair of trousers in order to hold them up” (sense I.6). In the more general sense of “strap, belt, or rope used in fastening or securing something” (sense I), the word had already been in the language since the early fourteenth century. The sense in which Jane Austen used it can’t have been exactly new, since she had to ask for the object when entering the shop and the shop assistant would have understood what she meant to be able to inform her that they didn’t have any, but this may indeed have been one of the earliest times such a homely object was referred to in writing. It will therefore be a matter of time before an earlier quotation is found. Netting silk, in the same sentence, might well deserve an independent entry in the OED, as I argue in In Search of Jane Austen (p. 135). In the form of silk netting the concept does have an entry in the online Design Encyclopedia.

Another interesting phrase in Letter 10 is Jane’s use of dropping out: “I had the dignity of dropping out my mother’s Laudanum last night,” she wrote, joking about taking on a doctor’s role in measuring out her mother’s medication. Only twelve drops, and no more of this addictive medicine. It is the last quotation in the OED of the transitive use of the verb to drop (sense II.11). The joke is one of many in the letter. Jokes are not easy to identify, since a lot of external context is needed to be able to assess them properly, and such context is not generally provided in Le Faye’s edition of the letters. But they are important, because they are normally indicative of an informal, intimate relationship between writer and sender. Another example is Jane Austen’s use of chaperon as a verb. The verb does occur in the OED, and with Jane Austen as a first user, but the quotation is from one of her novels, Sense and Sensibility, so its date is 1811. Here we thus have an antedating, from 1798, with one of her letters as a source! So, OED editors, there is work for you to be done, but if you add the relevant quotation, “Your letter was chaperoned here by one from Mrs Cooke”, please leave in the original first instance from the novel, because it would tell users of the dictionary that new words from Jane Austen’s language might travel the path from informal private usage to writing for publication. Important evidence of how language works.

As a final instance I want to discuss Jane Austen’s use of the word Dame in Letter 10. The word occurs three times in close proximity, which drew my attention to it: “Dame Tilbury’s daughter has lain-in”, “Dame Bushell washes for us only one week more” and “Dame Staples will supply the place of one [i.e. a maidservant]”. As usual, Le Faye’s edition offers no help; there is nothing in her generally very useful Subject Index under the entry “Domesticity, house-keeping” that deals with social titles or address forms of servants. The three women are identified in the equally (and phenominally!) useful Biographical Index, but only about Dame Staples do we find information on her social status: she was “a Steventon villager”, so someone having a different social status than Jane Austen and her family. Checking the word in the OED shows how over time the word underwent a decrease in status in its attributive function as “expressing rank or honour”, from “A form of address originally used to a lady of rank, or a woman of position” (sense II.5), through being “[p]refixed to the surname of a housewife, an elderly matron or schoolmistress” (II.6.c) to “A woman in rank next below a lady: the wife of a knight, squire, citizen, yeoman” (II.7.b). The latter two senses are labelled “archaic or dialect”, but Jane Austen’s use of the word indicates that a further lowering of referential status could be identified in her own local dialect. I’m often asked the question after a talk on the language of the letters if there is any dialect in the letters. The answer is “yes”, as indeed I discuss in my book (pp. 228–229), and here is another example, and there may well be more. But it is clear that extensive close reading of the letters is required in order to be able to identify such instances, and also that the OED is not always entirely helpful. This instance, I suggest, needs to be added as an additional dialectal use of the word in order to add to the continued history of dame. And who knows, further quotations may be found when specifically looking for them in private documents like Jane Austen’s letters.

Jane Austen, as I mention in the above powerpoint slide, is a good source for the OED, and extensive close reading of the letters will undoubtedly provide more examples of new or disappearing words. But sometimes quotations citing her as a source should be removed, as I also discuss in my book for the words mamalone and midgety (pp. 138–139). Both words are marked as “misreadings” in the dictionary and have since been corrected by Le Faye into mamalouc and nidgetty, respectively, but they still appear in the OED as individual entries, with single quotations from Jane Austen’s letters. Are the entries perhaps kept in because of Jane Austen’s status as a writer? The misreadings are not hers though, so they don’t illustrate her language use but earlier editorial mistakes. A related example of what is strictly speaking not Jane Austen’s own language either is the quotation illustrating the word itty, which merely reflects a young child’s pronunciation of little. The OED’s illustration, “My dear itty Dordy’s remembrance of me is very pleasing to me”, is from Letter 10, but the word already occurs in Letter 9, written a few days earlier, so strictly speaking, we have an antedating here: “I flatter myself that itty Dordy will not forget me at least under a week” (Letter 9). While I’m actually suggesting to replace the present “first” in the entry for itty, I also want to argue that the instance is placed between square brackets, because the words are not Jane Austen’s own but those of her three-year-old nephew George who, it appears, is mimicked by his fond aunt for referring to himself in such a cute way.

So even if I believe that Jane Austen is a great source for the OED, my analysis of the language of her letters, and for the present case study of Letter 10 in particular, suggests that much more is to be found if a linguistic close reading is carried out systematically. When attempting to do so the first major tool for analysis will be Le Faye’s annotated edition, and especially her highly informative indexes. Linguistically, however, the OED will be indispensible in such a project, which I expect will produce much detailed additional information on the meaning and social function of words at the time, as in the case of the word Dame. But the current presence of Jane Austen in the dictionary should be closely scrutinised as well, and non-words, recognised as misreadings that have meanwhile been corrected, had better be removed, while credit could at the same time be given to members in Jane Austen’s social network whose language she mimicked in her letters, no matter how young they were. Mimicry is something she regularly engaged in, and who knows what further discoveries will be made as a result of a further extensive linguistic close reading of the letters when her sources of mimicry are close scrutinised.