I’m teaching a course on Late Modern English letters this semester, for which all participants (as in earlier courses on the subject) have to write two blog posts on a topic relating to what we’re doing in the course. Here comes Katja (Ekaterina) Krokhina’s first blogpost.

Sourse: Wikipedia

It goes without saying that everybody who speaks English has heard of the adverb most. What comes to your mind first when you hear this word? The superlative form of comparison perhaps? How many of you, readers, have thought of most in the function of an adverbial intensifier? In this blog post, I would like to shed some light on most as an intensifier. In order to do so I will travel back in time, to the days of Charlotte Brontё (1816–1855).

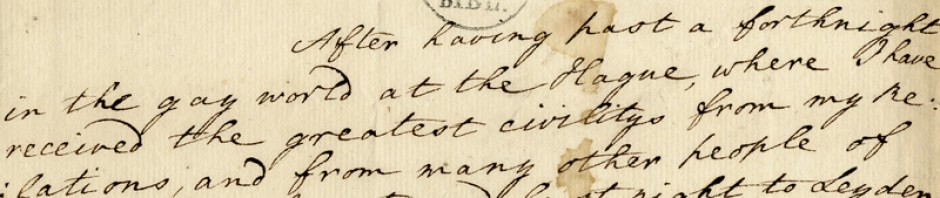

While reading Charlotte Brontё’s letters, I came across some unfamiliar examples related to the case of most. Here are some of them:

- I am most grieved (Charlotte Brontё to Ellen Nussey, 1836)

- On that day we shall all be most happy to see you, and till then believe me to be (Charlotte Brontё to Ellen Nussey, 1833)

- However I thank both you & your Mother for the invitation which was most kindly expressed (Charlotte Brontё to Ellen Nussey, 1839)

- Richard most kindly disbursed all the expenses (Charlotte Brontё to Ellen Nussey, 1833)

- I laughed most heartily at her graphic details (Charlotte Brontё to Ellen Nussey, 1836)

In these examples, Charlotte Brontё usesmost as an intensifier with a meaning that is close to very. But how come that nowadays this usage is not in favour anymore? This was exactly the question which I asked to myself. To see what scholars say about this question, I have done some research and here I am with the freshly baked answer.

Source: Wikipedia

Tauno Mustanoja (1912–1996), a philologist and scholar of Medieval and Middle English, together with the Dutch linguist Elly van Gelderen described the origin and historical route of the adverb most (2016: 328). According to Mustanoja and van Gelderen, most used to be common in early ME, but it gave its way to almost (all+most) after the middle of the thirteenth century. Although most never disappeared completely from the English language, this adverb bit by bit lost its intensifying function, starting to establish itself in the system of “multiple comparisons” (2016: 328). Following Mustanoja and van Gelderen, “multiple comparison” is defined as “the use of more and most with the inflectional comparative and superlative”, for example, “moste clennest flesch”. Later on, with the increasing use of the periphrastic system of comparison, the usage of most as a superlative became quite common from the fourteenth century onwards (Mustanoja). Nevertheless, this is a different story.

Going back to the topic of intensifiers in Charlotte Brontё’s correspondence, it should be said that she had two personal “favourites” among them: very and most. I am already looking forward to discussing these two intensifying adverbs in my next blog post, to see which one she preferred in her letters. For all that, it would be quite interesting to know if there are any people nowadays who still use most as an intensifier. Would it be acceptable to say, for example, it is most interesting or I think it is most exciting? Please let me know if you have any ideas on this topic.

References:

Brontë, C. The Letters of Charlotte Brontë: with a selection of letters by family and friends (1829−1847). M. Smith (ed.). Vol. 1. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

Mustanoja, T. F., & Gelderen, E. van (2016). A Middle English Syntax : Parts of Speech. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.