Cassandra Elizabeth, Jane Austen’s sister (1773–1845), not only left a Will but also a private document in the form of a letter to her brother Charles, in which she specified who were to inherit her most prized personal possessions. The contents of the letter are summarised in Deirdre Le Faye’s Chronology of Jane Austen and her Family 1600–2000 (2013), an amazing book because of its enormous scope and detailed descriptions of the documents relating to the Austen family. The book is a must for anyone doing research on Jane Austen and her close relatives.

I’m writing an article on Cassandra’s Will and several other wills, as a follow-up to the one I published in 2014 in English Studies on the Will of Jane Austen herself. Having submitted the article, I received suggestions for revision from two referees. All this would have been very helpful, were it not for the fact that the two most interesting articles mentioned were published in annual reports of the Jane Austen Society in the UK. These reports, however, are not generally available: my university libray doesn’t subscribe to it because you have to be a member of the society to be able to have asccess to them. The Jane Austen Society does give access to its annual reports online, but not beyond the year 2018, while the articles I needed were published in 2019 and 2022, respectively. So how could I follow up the referee’s suggestion to look at them? Fortunately, I remembered that a friend of mine had once mentioned that the best thing she’d ever done was to become a life member of the Society – and yes, she very willingly lent me the two reports I needed.

The two articles do indeed contain relevant material for my revised article, though I do think that they should have been more generally available to scholars working on the subject other than through the willingness of a friend I happen to have. I also think, having read both articles, that it wasn’t academically acceptable not to refer to my earlier publication on Jane Austen’s Will. It seems that we have to do here with two worlds that do not mix, which is not as it should be in academia.

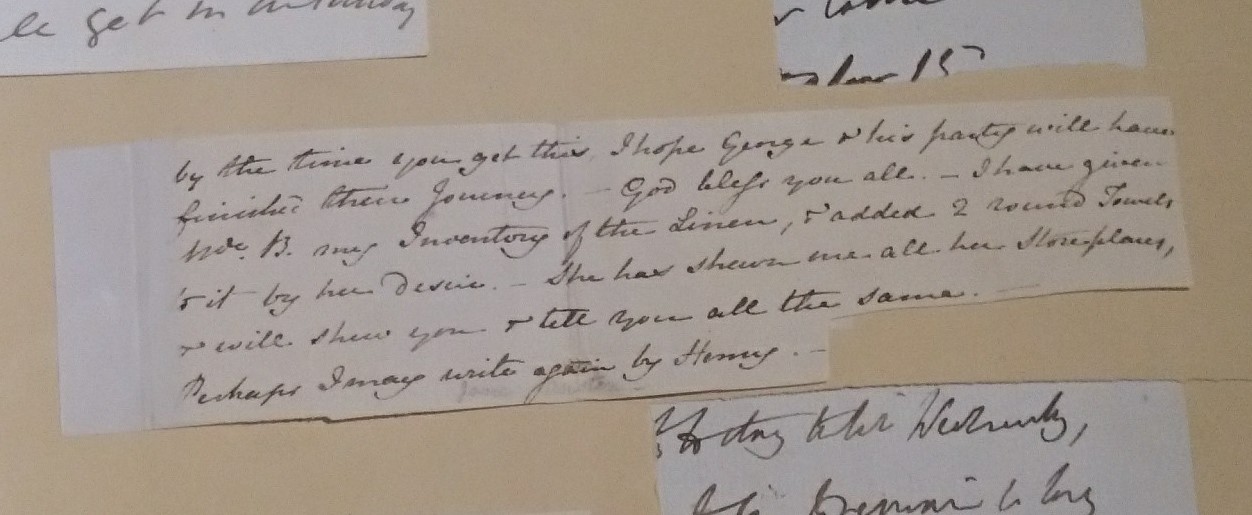

Be all that as it may, I made a really interesting (personal as well as academic) discovery, in that the most recent article of the two, by John Avery Jones, Devoney Looser and Peter Sabor called “Cassandra Austen’s last years and wishes, with new documents and transcriptions”, contains some fascinating material: a digitised image of the second page of Cassandra’s letter to Charles mentioned above, her “Letter of Wishes”, as the authors call it. Not many letters by Cassandra have come down to us (Jones et al., p. 33), so this felt like a unique opportunity to look at her letter writing in an original document, just as I had done for my book on Jane Austen, called In Search of Jane Austen. The Language of the Letters (2014). So I immediately transcribed it, despite the fact that the authors had done so themselves as well.

My transcription follows below. It differs from the one by Jones et al. in a number of ways. For one thing, mine is an attempt at a diplomatic transcription, and thus reproduces the lines as found in the original document. This means that Cassandra’s practice to indent new paragraphs has been retained, which makes the text easier to read to begin with. But also her language, so that it shows her use of long <s>, as in the Caſsandra (twice) and the word croſs. The authors silently substituted short <s> for it without mentioning that this is what they did when reproducing the text.

Why would it have been important to reproduce Cassandra’s use of long <s>? Because it shows that this feature, which was abolished by the printers around the year 1800, continued to occur in private documents like letters (see Fens-de Zeeuw and Straaijer 2012). Cassandra appears to have kept the spelling patterns she had been acquired in her youth, just as Jane did. This tells us something about her linguistic personality, as in the case of my study of Jane’s letters. For Cassandra, we don’t have as many letters available for anlysis as in Jane’s case, so this tiny piece of evidenc is very valuable indeed.

Language is hardly ever focused on in studies of Jane Austen and her work, which is why I decided to write my book on the language of her letters in the first place. And Jones et al. do not refer to Cassandra’s language in the letter they reproduced either. Yet at least two things can be said here that are of interest. To begin with, Cassandra varied in her use of the preposition to in constructions requiring an indirect object after the verbs bequeath, give or leave. Those instances without to would seem archaic to us today, and it may be that her variable usage reflects a change in progress at the time that deserves further study.

The second point of interest is her use of the word Hoop-ring. Not knowing what a hoop-ring was, I turned to the OED, which defines it as “A ring consisting of a plain band; (also) a finger-ring encircled with stones in a cut-down setting”. The OED also provides quotations, though only three of them, with the first being dated 1545 and the last one a1817, surely a significant date in this context. All instances are spelled without a hyphen, in contrast to what we find in Cassandra’s letter. The last quotation is from Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey. So with Cassandra’s usage of the word we have found a postdating for the OED by nearly thirty years! And perhaps the unhyphenated forms recorded by the OED represented the printers’ preference. Again, Cassandra’s usage cofirms the importance of studying private usage, which my be different from what we find in printed books.

So all in all, my plea here is for staying closer to an author’s original writing when reproducing their text (by for instance copying their indents and reproducing older spelling patterns but other features as well), even if their language use is not a main topic in the publication concerned. And secondly, what this brief piece shows is that even in a small text like part of a letter, it is worth looking at the author’s language in the context of the times in which it was produced. I at any rate feel that I’ve gained a tiny bit more insight into Cassandra’s personality.